After a two-month break from writing and a lot of integration during a 5000km trip across Australia from Melbourne to Darwin, I reconnect with my passion here. This new series of articles will truly mark the start of a long-term literary adventure, with pleasure and determination.

The second book to have had a profound impact on my life and which I would like to talk about here comes from the other side of the world, from the country where the sun rises, Japan.

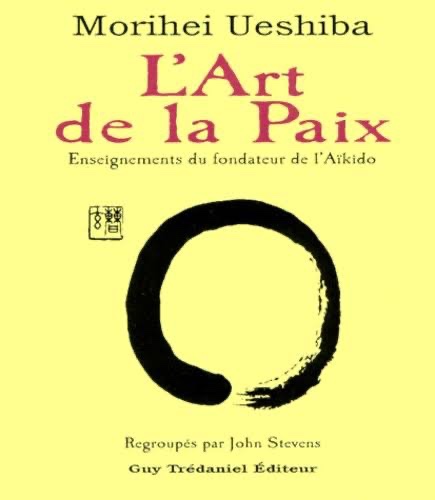

“The Art of Peace” was born from the teachings of the founder of Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969). It was published in 1992 by John Stevens.

This art takes the form of an achievement, of the union (Ai) of energies (Ki) leading to peace. The man behind this, Morihei Ueshiba, was nothing less than one of the greatest martial artists in history. At the age of 80, he was capable of disarming any attacker, knocking down several attackers, and pinning an opponent to the ground with a single finger. An invincible fighter, Morihei was above all a man of peace, hating fights, war and violence in all its forms. His path was that of Aikido, the path of the union of energies. The creation of this martial art was the fruit of a personal journey closely linked to the times of war which agitated his country at the time, and his participation in these armed conflicts gave him an experience of the challenges of duality and war in a very particular way.

A philosophy, a state of “being in the world”, a path of reconciliation outside of judgment but in the observation of what serves or harms us. This discipline is today unloved by many martial arts practitioners, also because it invites people to put an end to a confrontation as quickly as possible, using techniques that prevent any aesthetic glorification of violence. The conflict is stopped dead in its tracks, and peace imposes itself. There is neither animosity for his assailant, nor desire to hurt him, but simply the act of putting an end to the imbalance which leads to the confrontation.

In many Asian societies, we generally encounter much less school bullying or personal violence compared to our Western societies. Mainly because the majority of children, girls and boys alike, are educated to defend themselves and be respected, and thus the value of respect for everyone is still very significant today. It is never a gift for an abuser to receive no resistance. If we want to help this person understand that their actions are not for their benefit, that they are only expressing an inner unhappiness outside of themselves, it can be truly kind to put an end to the physical and mental oppression exerted through the use of the art of peace.

This martial art is mainly practiced on the tatami, but from there, it can take an essential place in our lives and in safeguarding the peaceful interactions we have with our peers.

In the future, I intend to practice this physical discipline and put myself even more at the service of others, with balance and compassion.

———

Après une pause de deux mois d’écriture et énormément d’intégration lors d’un voyage de 5000km à travers l’Australie de Melbourne à Darwin, je reconnecte à ma passion ici. Cette nouvelle série d’articles inscrira véritablement cette aventure littéraire dans la durée, avec plaisir et détermination.

La deuxième œuvre littéraire à avoir eu un profond impact dans ma vie et dont j’aimerais parler ici vient de l’autre bout du monde, du pays où le soleil se lève, le Japon.

« L’Art de la Paix » naît des enseignements du fondateur de l’Aïkido, Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969). Il fut publié en 1992 par John Stevens.

Cet art dont il est question prend la forme d’une réalisation, de l’union (Aï) des énergies (Ki) conduisant à la paix. L’homme derrière cet art, Morihei Ueshiba, ne fut ni plus ni moins que l’un des plus grands artistes martial de l’histoire. A 80 ans passés, il était capable de désarmer n’importe quel agresseur, de mettre à terre plusieurs assaillants, et de clouer d’un seul doigt un adversaire au sol. Invincible combattant, Morihei était par dessus tout un homme de paix détestant la bagarre, la guerre et la violence sous toutes ses formes. Sa voie était celle de l’Aïkido, la voie de l’union des énergies. La création de cet art martial fut le fruit d’un cheminement personnel étroitement lié aux temps de guerre qui agitaient son pays à son époque, et sa participation dans ces conflits armés lui offrit une expérience de la dualité et des enjeux de la guerre toute particulière.

Une philosophie, un « être au monde », une voie de réconciliation hors du jugement mais dans l’observation de ce qui nous sert ou nous dessert. Cette discipline est aujourd’hui mal aimée de nombreux pratiquants d’art martiaux, aussi parce qu’elle invite à faire cesser un affrontement de la plus rapide des manières, par des techniques qui empêchent toute glorification esthétique de la violence. Le conflit est stoppé net, et la paix s’impose d’elle même. Il n’y a ni animosité pour son assaillant, ni volonté de le blesser, mais simplement l’acte de mettre fin au déséquilibre qui amène à l’affrontement.

Dans un bon nombre de sociétés asiatiques, on rencontre en général moins d’harcèlement scolaire ou de violence à la personne comparé à nos sociétés occidentales. Principalement parce que la majeur partie des enfants, filles comme garçons, sont éduqués à se défendre et à se faire respecter, et ainsi la valeur du respect de chacun y est très prégnante encore aujourd’hui. Ce n’est jamais un cadeau pour un agresseur de ne recevoir aucune résistance, et à vrai dire si l’on souhaite aider cette personne à comprendre que ses actions ne sont pas à son avantage, qu’elle ne fait qu’exprimer un mal être intérieur au dehors d’elle même, il peut être réellement aimable de mettre fin à l’oppression physique et mentale exercée par l’utilisation de l’art de la paix.

Cet art martial se pratique principalement sur le tatami, mais depuis celui ci, il peut prendre une place essentiel dans nos vies et dans la sauvegarde des interactions paisibles que l’on a avec nos congénères.

Dans l’avenir, je compte bien pratiquer cette discipline physique et me mettre encore plus au service d’autrui, dans cet équilibre et cette compassion.

Vous êtes ici pour nul autre propos que de réaliser votre divinité intérieure et de manifester votre illumination innée. Cultivez la paix dans votre vie et appliquez-la vers tous ceux que vous rencontrez.

― Morihei Ueshiba, p. 13

Leave a comment